Goal

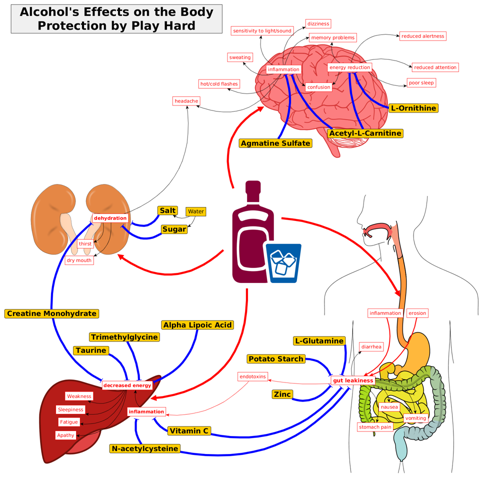

To abolish the toxic, unwanted effects of alcohol commonly known as a hangover by administration of commonly available dietary supplements without affecting greater damage in the long term.

Secondary-Goals

- Minimize the effort required to avert a hangover

- Keep the wanted effects of alcohol intact

- Focus on short term, acute effects

- Maximize subsequent exercise performance

- Avoid xenobiotic alterations to physiology

Current Formula

- glucose + glucose polymer

- saline + basic electrolyte solution

- glutamine (or complex protein)

- Creatine

- zinc

- N-acetylcysteine

- Alpha-Lipoic Acid

- Acetyl-L-carnitine

- Agmatine

- Ornithine

- Trimethylglycine

- Taurine

- Supplemental antioxidants: Vit E, C

- Magnesium

Version 0.1

Designed for a weekend trip of drinking and running followed by a Tough Mudder.

- 221g Electro-Endurance

- 468.17g base mix

- creatine

- ornithine

- ALA

- ALCAR

- TMG

- taurine

- glutamine

- Agmatine

- NAC

- 10 (50mg Zn) pills - 6.80g

- = 474.97g

- 47.5g each dose

- 23.75 each half dose

Ethanol Pharmacokinetics

The major gender difference was found after oral administration; although there were no gender differences in the peak alcohol levels (25.3 +- 1.3 mg/dl in women vs. 25.6 +- 2.1, in men), high ethanol levels persisted longer in women than in men. Baraona et al. (2001)

Several genetic variants exist which modify ethanol and acetaldehyde metabolism, but will not be discussed here. See Wall, Luczak, and Hiller-Sturmhöfel (2016)

Absorption

By contrast, the AUC after intravenous administration were similar in both genders (58.4 +- 3.3 vs. 53.7 +- 3.3). Baraona et al. (2001) Twenty percent of ethanol is absorbed in the stomach and 80% in the upper small intestine.J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) In general, there is little difference in the rate of absorption of the same dose of alcohol administered in the form of different alcoholic beverage i.e., blood ethanol concentration is not significantly influenced by the type of alcoholic beverage consumed. Cederbaum (2012) The rate of alcohol absorption depends on the rate of gastric emptying, the concentration of alcohol and is more rapid in the fasted state. Cederbaum (2012) The blood alcohol concentration is determined by the amount of alcohol consumed,the presence or absence of food and the rate of alcohol metabolism. Cederbaum (2012) Solid food intake can reduce the ethanol absorption rate by 30% and it has been suggested that this effect is due to the need for food digestion prior to absorption process. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) As such, if food is taken in as a liquid then it would not produce this effect [49, 54]. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) In both genders, the rate of gastric emptying decreases and the FPM increases by raising the imbibed ethanol concentration (Roine et al., 1991), but there is no evidence that this inhibitory effect of ethanol concentration is greater in male than in female subjects. Baraona et al. (2001)

Distribution

In the present study, the volume of alcohol distribution in women was 7.3% lower than in men, a difference too small to account for the changes in alcohol levels. Baraona et al. (2001) The equilibrium concentration of alcohol in a tissue depends on the relative water content of that tissue. Cederbaum (2012) The distribution of ethanol throughout the body is driven in direct proportion to water content of each tissue, especially at the ethanol steady-state. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) Since the blood flow to the brain remains relatively constant, changes in the blood concentration of ethanol are the most relevant factor influencing the amount of ethanol delivered to the brain and therefore for the different levels of brain intoxication [78–80]. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016)

Metabolism

Ninety percent of ethanol is metabolized in the liver after multiple passages but the lungs (especially via CYP2E1) also contribute to metabolism. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) In the gastric mucosa (and not in the small intestine), 5-10% of ethanol is metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase isoform (or isozyme) 7 (ADH7) and this is called gastric first pass metabolism of ethanol [3, 4]. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) The Km of CYP2E1 for ethanol is 10 mM, which is roughly one order of magnitude higher than that of ADH1. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) Therefore, CYP2E1 and catalase are the main pathways in the brain that metabolize ethanol to acetaldehyde, while ADH appears to play a minor role. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) The oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde can occur in the brain through pathways that involve catalase, cytochrome CYP2E1, and ADH. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) First pass metabolism of alcohol occurs in the stomach and is decreased in alcoholics. Cederbaum (2012) Alcohol metabolism is regulated by the nutritional state, the concentration of alcohol,specific isoforms of alcohol dehyrogenase, need to remove acetaldehyde and regenerate NAD and induction of CYP2E1. Cederbaum (2012) Whereas metabolism of the major nutrients is under hormonal control, e.g insulin/glucagon, leptin, catecholamine, thyroid hormones, generally, there is little hormonal regulation to pace the rate of alcohol elimination. Cederbaum (2012) Animals with small body weight metabolize alcohol at faster rates than larger animals e.g. the rate of alcohol elimination in mice is 5 times greater than the rate in humans. Cederbaum (2012) However, it is important to note that alcohol-derived calories are produced at the expense of the metabolism of normal nutrients since alcohol will be oxidized preferentially over other nutrients (19–23). Cederbaum (2012) The Km of CYP2E1 for alcohol is 10 mM ,10-fold higher than the Km of ADH for ethanol but still within the range of alcohol concentrations seen in social drinking. At low alcohol concentrations, CYP2E1 may account for about 10% of the total alcohol oxidizing capacity of the liver. Cederbaum (2012) Acetaldehyde can also be oxidized by aldehyde oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and by CYP2E1, but these are insignificant pathways. Cederbaum (2012) The overall significance of first pass metabolism by the stomach is controversial. Cederbaum (2012) MEOS has a higher Km than ADH in oxidizing alcohol and oxidizes alcohol to generate acetaldehyde. Leung and Nieto (2013) Consequently ADH3 plays a more important role in the metabolism of alcohol at high concentrations. In addition, microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) and catalase contribute to the metabolism of alcohol in specific circumstances, such as high ethanol concentrations [48, 60]. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016)

ADH

Nonetheless, ADH4 inhibition avoids the synaptic dysfunction associated with severe alcohol intoxication in the hippocampus [89]. @HernandezLipidsOxidativeStress2016 Liver alcohol dehydrogenase is the major enzyme system for metabolizing alcohol; this requires the cofactor NAD and the products produced are acetaldehyde and NADH. Cederbaum (2012) There is, however, no correlation between the alcohol dehydrogenase activity measured in vitro and the rate of ethanol oxidation in vivo or in liver slices [2,3,4]. As the activity of the enzyme does not appear to be the rate-limiting factor, it is assumed that the oxidation of NADH is rate- limiting for the ethanol oxidation in vivo. Thieden et al. (1972) Moreover, a small amount of ethanol can be oxidized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) classes I and IV [52, 55] in the stomach and intestine. This acetaldehyde can be absorbed along with ethanol and metabolized by the liver or other tissues. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) Most first pass metabolism occurs in the liver [49, 55] and the rate-limiting step is the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde. This reaction is catalyzed by proteins of the ADH family [56], of which class I (ADH1) and III (ADH3) enzymes metabolize ethanol in the liver [57, 58]. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) Indeed, ethanol is primarily bioactivated (92-95%) by cytosolic (especially hepatic) ADH1B into acetaldehyde, which has proved to have mutagen and carcinogen effects [1]. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) The gastric mucosa expresses three classes of ADH isozymes in a decreasing order of affinity for ethanol: gamma-ADH, a class I isozyme also present in the liver, sigma-ADH, a class IV ADH characteristic of the upper digestive tract, and chi-ADH, a class III isozyme found in most tissues. we found a 58% reduction in class III (or chi -) ADH activity in women compared with men (Fig. 3), Baraona et al. (2001)

ALDH

The acetaldehyde is further oxidized to acetate, the same final metabolite produced from all other nutrients-carbohydrates, fats and proteins; the acetate can be converted to CO2, fatty acids, ketone bodies, cholesterol and steroids. Cederbaum (2012) The low Km mitochondrial ALDH oxidizes most of the acetaldehyde produced from the oxidation of alcohol, although in human liver, the class I cytosolic ALDH may also contribute (75). Cederbaum (2012) In general, the capacity of ALDH to remove acetaldehyde exceeds the capacity of acetaldehyde generation by the various pathways of alcohol oxidation. Therefore, circulating levels of acetaldehyde are usually very low. Cederbaum (2012) The acetaldehyde produced by the oxidation of ethanol is thereafter transformed to acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) [61], which can be further metabolized through the tricarboxylic acid cycle to generate energy, or these metabolites can be deposited in the plasma [62, 63]. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016)

CYP2E1

Oxidation of alcohol by cytochrome P450 pathways, especially CYP2E1 which is induced by alcohol, are secondary pathways to remove alcohol especially at high concentrations. Cederbaum (2012) Among the cytochrome P450 family, CYP2E1 has been identified as the most relevant for ALD as it is highly inducible and it has high catalytic activity for alcohol [18]. @leung_cyp2e1_2013 CYP2E1 is mainly expressed in the liver, with hepatocytes showing the highest expression, but it is also located in other organs such as the brain and intestine. CYP2E1 is mainly located within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) although it is also expressed in the mitochondria [23]. @leung_cyp2e1_2013 This indicates that CYP4A induction could be an alternative pathway when CYP2E1 is less available [28]. @leung_cyp2e1_2013 CYP2E1 enzyme is induced in response to chronic drinking and it may contribute to the increased rates of ethanol elimination in heavy drinkers. Some endogenous substrates for CYP2E1 include acetone and fatty acids, both of which are abundant in the brain [95]. @HernandezLipidsOxidativeStress2016 At high blood ethanol levels, the microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system (CYP2E1 isoform, located in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum) also has an important role. Ethanol itself induces the activity of CYP2E1, and therefore also influences the metabolism of other xenobiotics ( e.g. paracetemol and cocaine) J Dinis-Oliveira (2016)

Catalase

Studies using inhibitors of catalase and acatalasemic mice revealed that catalase is responsible for approximately half of the ethanol metabolism occurring in the CNS [91]. @HernandezLipidsOxidativeStress2016 Catalase pathway is limited by the rather low rates of H2O2 generation produced under physiological cellular conditions (less than 4 umol/g liver/hr, only 2% that of alcohol oxidation) and appears to have an insignificant role in alcohol oxidation by the liver. Cederbaum (2012) Indeed, acetaldehyde production in the brain in vivo depends on catalase activity [85, 93] and catalase appears to be expressed in all neural cells. Hernández, López-Sánchez, and Rendón-Ramírez (2016) Catalase is of minor importance (responsible for approximately 5%) in the metabolism of ethanol. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016)

Elimination

Alcohol elimination now follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics; the rate of change in the concentration of alcohol depends on the concentration of alcohol and the kinetic constants Km and Vmax (23,24). Cederbaum (2012) Unchanged ethanol is eliminated in small quantities (approximately 5% of orally absorbed ethanol) by the kidneys (0.5–2%), lungs (1.6–6%) and skin (<0.5%) [4]. J Dinis-Oliveira (2016) We confirmed the observation by others (Dubowski 1976; Mishra et al., 1989) that the rate of ethanol oxidation, a function predominantly exerted by the liver, is faster in women than in men. In the present study, the maximal rate of elimination (VMAX) was 10% higher in women than in men. Baraona et al. (2001) This resulted in a 47% greater AUC after oral ethanol in women than in men (45.9 +- 3.4 mg/dl 3 h vs. 31.2 +- 7; p , 0.01). Baraona et al. (2001)

Byproducts

although metabolites of ethanol, like acetate, can also reach the brain as products of first pass metabolism [85]. @HernandezLipidsOxidativeStress2016 A significant body of evidence indicates that acetaldehyde is accumulated in the colonic lumen due to enteric microbial fermentation (22, 23). Basuroy et al. (2005) Intracolonic acetaldehyde level is dramatically increased by alcohol consumption (6, 20, 27). Basuroy et al. (2005) In the gastrointestinal tract, acetaldehyde can be generated from ethanol through mucosal and/or bacterial alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) (Seitz and Oneta, 1998). Purohit et al. (2008) Accumulation of acetaldehyde in the colonic lumen could be due to low efficiency of bacterial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to metabolize acetaldehyde in the colon (Nosova et al., 1998). Purohit et al. (2008)

Unsorted

Catalase, a heme containing enzyme, is found in the peroxisomal fraction of the cell. Cederbaum (2012) Fatty acid ethyl ester synthases catalyze the reaction between ethanol and a fatty acid to produce a fatty acyl ester. Cederbaum (2012)

Interactions by Ethanol and Byproducts

alcohol hangover does not have a single cause that leads to one condition, but should be viewed as a syndrome. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012)

Treatment of macrophages with physiologically relevant doses (25 mM, 50 mM, 75 mM) of alcohol for 15 min significantly increased HSF-binding activity (Fig. 1B). A combination of LPS with alcohol (50 mM and 75 mM) resulted in a further augmentation of HSF DNA binding as indicated in the bar graph (Fig. 1B, lower panel), as compared with LPS or alcohol treatment alone (Fig. 1B). Mandrekar et al. (2008) Specifically, we show that in monocytes and macrophages, short-term alcohol increases HSF-1-binding activity and induces hsp70 mRNA and protein. Mandrekar et al. (2008) In neuronal cells, acute and chronic alcohol exposure induces hsp genes such as hsp70, hsp90, glucose-regulated protein (grp)78, and grp94 via HSF-1 activation [20, 37, 38]. Mandrekar et al. (2008) Whereas at first interpreted as a signal of cellular adaptation to stress and protection from the injury, it is now being recognized that hsps and its transcription factor HSF-1 can also contribute to cellular injury [40]. @mandrekar_alcohol_2008 Here, we show that although short-term alcohol alone does not affect hsp70, LPS-induced hsp70 promoter activity, mRNA, and protein are increased in macrophages. Hsp70 induction is regulated by cooperation from other transcription factors such as STAT1, which interacts directly with HSF-1 to induce hsp70 [45]. @mandrekar_alcohol_2008 Here, it is likely that acute alcohol directly increases transcription of hsp70, which in turn could repress TNF-\(\alpha\) gene expression. Hsp70 could act via sequestration of NF-\(\kappa\)B in the cytoplasm [43, 44] or direct binding to TNF-\(\alpha\)and inhibition of its release [42] in acute alcohol exposure. Mandrekar et al. (2008) Thus, our results suggest that hsp90 inhibition may prevent the alcohol-induced augmentation of LPS-induced NF-\(\kappa\)B-binding activity and TNF-\(\alpha\)and subsequently reduce inflammation in ALD. Hence, we propose that hsp90 plays an important role in alcohol-induced inflammation. Mandrekar et al. (2008) 1) acetaldehyde inhibits protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase) activity and slightly elevates the activation of p60c-Src and p125FAK, resulting in an increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human colonic mucosa; 2) acetaldehyde increases tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin, E-cadherin, and \(\beta\)-catenin; 3) acetaldehyde reduces the levels of detergent-insoluble fractions of TJ and AJ proteins, leading to redistribution of these proteins from the intercellular junctions; Basuroy et al. (2005) Dr. Muralidharan hypothesized that TLR4 tolerance following alcohol exposure is mediated by stress proteins, including heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) and heat shock protein 70 (hsp70). Primary human monocytes or murine RAW macrophages treated with LPS showed a reduction in proinflammatory mediator (IL-6, TNF\(\alpha\), IL-1\(\beta\)) release following 25 mM alcohol exposure, while the expression of HSF1 and hsp70 mRNA was increased subsequent to alcohol exposure. Morris et al. (2015) Female mice displayed a heightened inflammation after alcohol, and this may contribute to increased susceptibility to alcohol-related neurotoxicity in females. Morris et al. (2015) Low alcohol consumption improved left ventricular contractility. This was accompanied by reduced hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) superoxide dismutase (SOD-3) activity, and elevated nuclear respiratory factors (NRF)1/2, Forkhead box proteinO1 (FOXO-1), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-\(\kappa\)B), and Akt expression, as well as an increase in cardiomyocyte survival. In contrast, high blood alcohol led to an increase in H2O2 level and SOD-3 activity, and a decrease in NRF1/2, FOXO-1, NF-\(\kappa\)B, and Akt expression, resulting in a decrease in cardiomyocyte survival. Together, these findings suggest that low and high blood alcohol may produce opposite effects on cardiomyocytes. Morris et al. (2015) There was a significant increase in PLAT permeability in alcohol-exposed mice. PLAT cytokine (IL-6, TNF\(\alpha\), and GM-CSF) expression was unchanged 30 minutes following alcohol treatment; however, 24 hours after alcohol exposure, cytokine expression was higher compared to control animals. PLAT immunohistochemistry data revealed a significant increase in mast cells and neutrophils in rats after alcohol exposure. These results suggest that acute alcohol exposure results in increased mesenteric lymphatic permeability and PLAT inflammation. Morris et al. (2015) Drowsiness and impaired cognitive functioning are the two dominant features of alcohol hangover. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) Rohsenow et al. (2007) also found being tired (fatigue) and thirsty as most severe hangover symptoms, although in opposite order of the results of this survey. This is remarkable, since it has been suggested that these symptoms are primarily the result of sleep deprivation and dehydration, respectively (Verster et al., 2010). Yet, Rohsenow et al. (2007) controlled for sleep and liquid intake on the alcohol and placebo nights. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) The authors reported that nausea, fatigue, thirst and tension correlated best with the overall hangover severity (Ylikahri et al., 1974). Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) The symptoms were categorized according to their assumed common biological relationship and include constitutional, pain, gastrointestinal, sleep and biological rhythms, sensory, cognitive, mood and sympathetic hyperactivity. The categorization was however not derived from data. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) Most commonly reported and most severe hangover symptoms were fatigue (95.5%) and thirst (89.1%). Factor analysis revealed 11 factors that together account for 62% of variance. The most prominent factor ‘drowsiness’ (explained variance 28.8%) included symptoms such as drowsiness, fatigue, sleepiness and weakness. The second factor ‘cognitive problems’ (explained variance 5.9%) included symptoms such as reduced alertness, memory and concentration problems. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) a loss of epithelium at the tips of the villi, haemorrhagic erosions and even haemorrhage in the lamina propria (Bode et al., 2001). Similar lesions were observed in volunteers 2-3 hours after ingestion of alcohol (15-20%, v/v) and in recently drinking alcohol abusing subjects (Bode et al., 2001). Purohit et al. (2008) The mucosal damage caused by alcohol might result in an impaired intestinal barrier function, enabling toxins of gut-inhabiting bacteria such as endotoxins to enter the systemic circulation and to contribute to liver injury after alcohol consumption. Purohit et al. (2008) An ethanol-induced increase in intestinal permeability was also reported in human subjects when smaller molecules were used as a permeability probe. Purohit et al. (2008) These studies clearly indicate that alcohol can increase intestinal permeability to various macromolecules including endotoxin. Purohit et al. (2008) Furthermore, plasma endotoxin levels were also significantly elevated in actively drinking alcoholics without evidence of liver disease (Bode et al., 1987; Nolan, 1989), suggesting that alcohol itself can increase endotoxin levels presumably via increasing intestinal permeability to endotoxin. Purohit et al. (2008) In mice, plasma endotoxin levels were significantly elevated 1.5 hour after intragastric administration of 6g/kg ethanol by gavage, and this was associated with significant small intestinal injury (Lambert et al., 2003). Purohit et al. (2008) These mice developed significant liver injury 6 hours after ethanol administration, suggesting that alcohol is the causal factor for endotoxemia. Both human and animal studies suggest that alcohol mediates the transfer of endotoxin from intestine to the liver that results in the elevation of plasma enotoxin levels. Purohit et al. (2008) These studies suggest that alcohol may not only increase intestinal permeability to peptidoglycan, but also works synergistically with it to induce liver injury. Purohit et al. (2008) In an intragstric infusion rat model of alcoholic liver injury, sterilization of intestine by antibiotics significantly attenuated liver injury by reducing plasma levels of endotoxin (Adachi et al., 1995), and in the same model, similar results were obtained by simultaneous feeding of probiotic lactobacillus GG bacteria (competitive inhibitor of Gram negative bacteria) to the rats (Nanji et al., 1994). Purohit et al. (2008) However, ethanol up to 5% concentration failed to increase paracellular permeability, suggesting that ethanol metabolism to acetaldehyde is required for the action. Purohit et al. (2008) This study showed that ethanol increased paracellular permeability at 7.5% concentration. Purohit et al. (2008) The importance of ethanol metabolism into acetaldehyde was further confirmed when acetaldehyde, and not ethanol, was shown to increase mucosal permeability in proximal rat colonic strips Purohit et al. (2008) In this study, ethanol exposure (1%, 2.5%, and 15%) increased expression of iNOS and increased production of NO and superoxide. Purohit et al. (2008) These results suggest that NO and superoxide anion generated in response to ethanol exposure may react with each other to form peroxynitrite which in turn may cause damage to microtubule cytoskeleton and subsequently disrupt intestinal barrier function. Purohit et al. (2008) Overgrowth of Gram negative bacteria can result in increased production of endotoxin which can escape into portal circulation leading to increased plasma levels of endotoxin. Purohit et al. (2008) These studies suggest that chronic alcohol abuse can promote bacterial growth in the intestine; Purohit et al. (2008) Since the ALDH reaction occurs largely in the mitochondria, the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH redox ratio will be lowered. Cederbaum (2012) Since the ADH reactions occur in the cytosol, the cytosolic NAD+/NADH redox ratio will be lowered. This ratio is reflected by the pyruvate/lactate ratio because of the reaction. Cederbaum (2012) Because the ADH and ALDH2 reactions reduce NAD+ to NADH, the cellular NAD+/NADH redox ratio is lowered as a consequence of ethanol metabolism. Cederbaum (2012) Important reactions inhibited because of this decreased NAD+/ NADH redox ratio are: * Glycolysis * Citric Acid Cycle (ketogenesis favored) * Pyruvate Dehydrogenase * Fatty Acid Oxidation * Gluconeogenesis Cederbaum (2012) Acetaldehyde derived from catalase-dependent oxidation of alcohol in the brain has been suggested to play a role in the development of tolerance to alcohol, to voluntary ethanol consumption and to the positive reinforcing actions of ethanol, perhaps via interaction with catecholamines to produce various condensation products. Cederbaum (2012) Fatty acid ethyl esters can be toxic, inhibiting DNA and protein synthesis. When oxidative metabolism of ethanol is blocked, there is an increase in ethanol metabolism to the fatty acid ethyl ester. Cederbaum (2012) SOME SUGGESTED CAUSES FOR ALCOHOL TOXICITY - Redox state changes in the NAD/NADH ratio - Acetaldehyde formation - Mitochondrial damamge - Cytokine formation (TNF\(\alpha\)) - Kupffer cell activation - Membrane actions of ethanol - Hypoxia - Immune actions - Oxidative stress Cederbaum (2012) CYTOCHROME P4502E1 (CYP2E1) - A minor pathway for alcohol metabolism - Produces acetaldehyde, 1-hydroxyethyl radical - Responsible for alcohol-drug interactions - Activates toxins such as acetaminophen,CCl4, halothane,benzene,halogenated hydrocarbons to reactive toxic intermediates - Activates procarcinogens such as nitrosamines, azo compounds to active carcinogens - Activates molecular oxygen to reactive oxygen species such as superoxide radical anion, H202, hydroxyl radical SUGGESTED MECHANISMS FOR METABOLIC TOLERANCE TO ALCOHOL - Induction of alcohol dehydrogenases - Increased shuttle capacity - Increased reoxidation of NADH by mitochondria - Induction of CYP2E1 - Hypermetabolic state - Increased release of cytokines or prostaglandins which elevate oxygen consumption by hepatocytes Cederbaum (2012) However, it is important to note that alcohol-derived calories are produced at the expense of the metabolism of normal nutrients since alcohol will be oxidized preferentially over other nutrients (19–23). Cederbaum (2012)

Supplements

both EGF and l-glutamine prevent the acetaldehyde-induced changes in protein tyrosine phosphorylation, the levels of detergent-insoluble TJ and AJ proteins, and redistribution of these proteins from the intercellular junctions. Basuroy et al. (2005) The protective effect of l-glutamine on acetaldehyde-induced permeability is mediated by EGF-receptor tyrosine kinase activity (25). Basuroy et al. (2005)

These findings suggest that alcohol may accentuate gastrointestinal blood loss associated with unbuffered aspirin ingestion. Goulston and Cooke (1968)

Vitamin C

Anti-oxidant prevent oxidative adducts Only works as preloaded

Creatine

cellular hydration assorted effects

Taurine

nAC taurine release preload SAMe and GSH preservation Liver oxidative stress

SAMe

Methylation Methionine metabolism preservation - too expensive

Aspirin

COX inhibitor, nonselective gastric ADH inhibitor minor uncoupling effects in mitochondria Aspirin can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding -> Only if really bad hangover…

Zinc

gut disfunction prevention immune modulation Taken before to inhibit ethanol induced gut permeability

Zinc-carnosine (expensive)

- prep according to EP0303380B1

- dose

- 75 mg oral rinse split 4/day

- 150 mg/d

Melatonin

brain SCN clock changes

Ornithine

pH modulation Ammonia recycling

Glutamine

Gut dysfunction prevention

Glucose

Hypoglycemia, short term

Glucose Polymer

Hypoglycemia, long lasting

Fructose/Sucrose

NADH->NAD+ conversion substrate after

Saline (Banana Bag)

Hydration status General health

Beta-Alanine

Pre-loaded pH buffer in muscle Or canosine…

N-acetylcysteine

intestinal antioxidant glutathione substrate

Alanine

gut tight junction activation

Leucine

gut tight junction activation

Curcumin

Grape Seed Extract

iNOS inhibition

Agmatine

iNOS and peroxynitrite reduction Neurotransmitter

Acetyl-L-carnitine

Mitochondria transport and uncoupling

Alpha-Lipoic Acid

Fe sequestration in mitochondria glutathione upregulation AMPK inhibition/leptin mimesis

Malate

malate-aspartate shuttle Oat supplementation ameliorated all of these changes (Keshavarzian et al., 2001). Studies are required to understand the mechanisms by which oat supplement preserves intestinal permeability. Purohit et al. (2008) Zinc supplementation attenuated ethanol-induced increases in serum endotoxin levels, serum ALT activity, and hepatic TNF-\(\alpha\)levels. These changes were associated with prevention of ethanol-induced liver injury (Lambert et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 2004). Purohit et al. (2008) These results suggest that zinc brought these changes, at least in part, by preventing ethanol-induced transfer of endotoxin from intestine to circulation which could be ascribed to preservation of intestinal morphology and permeability. Purohit et al. (2008) Pretreatment with iNOS inhibitor (L-N6-1-iminoethyl-lysine), peroxynitrite scavengers (urate or L-cysteine) or superoxide anion scavenger (superoxide dismutase) attenuated the damage caused by ethanol. Purohit et al. (2008) Suppressing the growth of Gram negative bacteria in the intestine may reduce the amount of endotoxin which in turn may attenuate endotoxin-associated organ damage. Purohit et al. (2008) Whether probiotic treatment can attenuate ALD in humans needs further investigation. Purohit et al. (2008) it was shown that that Na+ - coupled nutrient (glucose, alanine, or leucine) transport triggers contraction of perijunctional actomyosin, thereby increasing intestinal tight junction permeability and enhancing absorption of nutrients (Madara and Pappenheimer, 1987). Purohit et al. (2008) Agents or conditions which enhance reoxidation of NADH by the respiratory chain can increase the rate of alcohol metabolism e.g. uncoupling agents can accelerate ethanol oxidation in the fed metabolic state (38,39). Cederbaum (2012) Several drugs, including H2 receptor blockers such as cimetidine or ranitidine, or aspirin inhibit stomach ADH activity. This will decrease first pass metabolism by the stomach, and hence, increase blood alcohol concentrations. Cederbaum (2012)

Appendix A: Metadata on Studies

A total of 1410 participants completed the questionnaire, of which 56.1% (n = 791, 31.3% men and 68.7% women) had experienced at least one hangover during the last month. Penning, McKinney, and Verster (2012) Mice were treated with three intragastric doses of zinc sulfate at 5 mg zinc element/kg each dosing, with an interval of 12 hours, prior to acute ethanol challenge with a single oral dose of 6 g/kg ethanol. Purohit et al. (2008)

References

[ALD]: Alcoholic Liver Disease ADH: Alcohol Dehydrogenase *ALDH: Aldehyde Dehydrogenase

Baraona, Enrique, Chaim S. Abittan, Kazufumi Dohmen, Michelle Moretti, Gabriele Pozzato, Zev W. Chayes, Clara Schaefer, and Charles S. Lieber. 2001. “Gender Differences in Pharmacokinetics of Alcohol.” Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 25 (4): 502–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02242.x.

Basuroy, S., P. Sheth, C. M. Mansbach, and R. K. Rao. 2005. “Acetaldehyde Disrupts Tight Junctions and Adherens Junctions in Human Colonic Mucosa: Protection by EGF and L-Glutamine.” American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 289 (2): G367–G375. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00464.2004.

Cederbaum, Arthur I. 2012. “ALCOHOL METABOLISM.” Clinics in Liver Disease 16 (4): 667–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002.

Goulston, Kerry, and Allan R. Cooke. 1968. “Alcohol, Aspirin, and Gastrointestinal Bleeding.” Br Med J 4 (5632): 664–65. http://www.bmj.com/content/4/5632/664.short.

Hernández, José A., Rosa C. López-Sánchez, and Adela Rendón-Ramírez. 2016. “Lipids and Oxidative Stress Associated with Ethanol-Induced Neurological Damage.” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1543809.

J Dinis-Oliveira, Ricardo. 2016. “Oxidative and Non-Oxidative Metabolomics of Ethanol.” Current Drug Metabolism 17 (4): 327–35. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cdm/2016/00000017/00000004/art00005.

Leung, Tung-Ming, and Natalia Nieto. 2013. “CYP2E1 and Oxidant Stress in Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Journal of Hepatology 58 (2): 395–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.018.

Mandrekar, Pranoti, Donna Catalano, Valentina Jeliazkova, and Karen Kodys. 2008. “Alcohol Exposure Regulates Heat Shock Transcription Factor Binding and Heat Shock Proteins 70 and 90 in Monocytes and Macrophages: Implication for TNF-\(\alpha\) Regulation.” Journal of Leukocyte Biology 84 (5): 1335–45. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0407256.

Morris, Niya L., Jill A. Ippolito, Brenda J. Curtis, Michael M. Chen, Scott L. Friedman, Ian N. Hines, Gorges E. Haddad, et al. 2015. “Alcohol and Inflammatory Responses: Summary of the 2013 Alcohol and Immunology Research Interest Group (AIRIG) Meeting.” Alcohol 49 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.018.

Penning, Renske, Adele McKinney, and Joris C. Verster. 2012. “Alcohol Hangover Symptoms and Their Contribution to the Overall Hangover Severity.” Alcohol and Alcoholism 47 (3): 248–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/ags029.

Purohit, Vishnudutt, J. Christian Bode, Christiane Bode, David A. Brenner, Mashkoor A. Choudhry, Frank Hamilton, Y. James Kang, et al. 2008. “Alcohol, Intestinal Bacterial Growth, Intestinal Permeability to Endotoxin, and Medical Consequences.” Alcohol 42 (5): 349–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.131.

Thieden, Herluf ID, Niels Grunnet, Stig E. Damgaard, and Leif Sestoft. 1972. “Effect of Fructose and Glyceraldehyde on Ethanol Metabolism in Human Liver and in Rat Liver.” The FEBS Journal 30 (2): 250–61. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb02093.x/full.

Wall, Tamara L., Susan E. Luczak, and Susanne Hiller-Sturmhöfel. 2016. “Biology, Genetics, and Environment.” Alcohol Research : Current Reviews 38 (1): 59–68. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4872614/.